In our continuing journey through Renaissance Venice, we come to an apothecary shop. By the way, for anyone just stumbling over this entry, I’ve been doing a series of posts on my inspiration/research for the Mircea Basarab novel Masks. There’s a category on the sidebar to give you all of the posts.

Apothecaries in Venice sold a variety of items, from medicines and cosmetics to spices and sugars, and from ink and paper to wine and syrups. Basically, the division went like this: If something was sold in bulk (like rice), it was the purview of the grocers; if it was fresh foodstuffs (like fish or vegetables), it was sold in open market stalls. But if it was purchased in small amounts, was expensive and/or rare, or was supposed to be consumed for health reasons, it was probably sold by an apothecary.

Apothecaries mixed their own preparations, so a good part of their day was spent grinding up ingredients. Apprentices were usually stuck with this job, but in the pic above a local beggar has been given the task as a form of charity. Just what he was grinding depended on the shop, because Renaissance-era apothecaries tended to specialize. And nowhere was that more true than in Venice.

Vendecolori, for instance, were a type of apothecary unique to Venice which dealt mainly in pigments. Many artists made a long and costly trip to Venice every year because it was known to have the best materials. The queen of them all was ultramarine, made from ground up lapis lazuli. The name means “over the sea” because it had to be imported from mines in distant Afghanistan.

Raw lapis lazuli (top left), ultramarine in pigment form (bottom left), and used on Mary’s robes in a Renaissance painting. The gold leaf you see in the painting was actually cheaper than the ultramarine.

Top grade ultramarine cost 11 solidi (or $330.00 in our money) an ounce. It was so dear that it was usually reserved for the robes of the Virgin, and contracts for a painting often specified exactly how much ultramarine would be needed. Use less than had been paid for and your client would not be happy!

Other apothecaries specialized in candies, cakes and syrups, since sugar was believed to have medicinal properties. Pregnant women, for instance, were often prescribed marzipan to help with nausea, and cold sufferers would be given candies to relieve sore throats. Speaking of marzipan, did you know that Leonardo Da Vinci started his artistic career by making marzipan figurines for the prince of Milan? He liked marzipan because it was easy to shape. His client liked it for other reasons, as Leonardo famously (and angrily) wrote:

“I have observed with pain that my signor Ludovico and his court gobble up all the sculptures I give them, right to the last morsel, and now I am determined to find other means that do not taste as good, so that my works may survive.”

Yet, when he was later working for Lorenzo de Medici in Florence, he made the same mistake. And the same thing happened to Leonardo’s beautifully sculpted models of military fortifications. Which apparently looked good enough to eat!

Apothecaries served candy in paper spills, like the shop owner is handing to the man above. Nougat and suckets (candied fruit or fruit peel) were popular varieties.

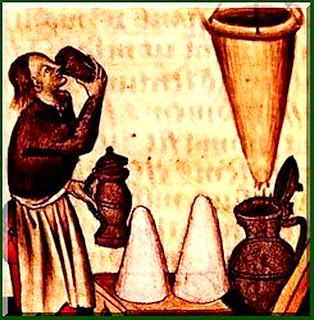

Along with candy, cakes and syrups, apothecaries specializing in the sale of sugar also provided the raw stuff, imported from the Middle East and, especially, from the island of Crete. Venetian families, like the Cornaros in the 14th century, had large plantations on Crete devoted to producing sugarcane. The juice from the cane was processed and then molded into conical loaf shapes for easy transport. A popular hat at the time was called a sugarloaf after the shape of the cake, which can be seen in the pic below.

Apothecaries were also the creators of some of the most spectacular banquet decorations of the day. Sugar sculpture, or spongade as it was known in Venice, became a popular way to show off. Sugar was expensive enough that it was usually kept under lock and key, so being able to waste large amounts on decoration was a sign of a person’s wealth. As a result, elaborate sugar sculptures were typically used to impress visitors, such as Henry III of France, who passed through Venice in 1574 on the way to his coronation.

A banquet was held in Henry’s honor, with sugar sculptures designed by artist Jacopo Sansovino and created by a local apothecary, Niccolo della Cavalliera. They were the usual massive creations, gilded or silvered as well as painted, that frequently populated the dining rooms of Venice: sailing ships, life-sized statues of popes and doges, Venetian lions and mythical beasts. And they were all impressive. But the real test of Venetian artistry came when the king visited the Arsenal shipyard for a mid-day meal a few days later, and picked up his napkin. And had it crack in his hands because it was made out of sugar. As was the tablecloth. And the bread. And the plates. The whole table was one giant sugar confection, but such was the artistry of the Venetians that he’d had to touch it to be able to tell.

And last, but definitely not least, apothecaries were best known for specializing in medicine, acting like our modern pharmacists. If pharmacists regularly used dung, saliva, powdered gemstones and cut up vipers in their concoctions, that is. But the idea was the same: a physician would prescribe a medicine, which you would go to an apothecary to buy.

Some of the medicines in use, like medicinal rhubarb imported from China, were at least harmless. And others may have even helped in some cases (cumin aids in digestion, some herbs had antiseptic qualities, and chicken soup was often prescribed for colds!) But others actually made the sufferer sicker by including toxins such as mercury or lead. Either way, medicines tended to be expensive, with one Florentine silk merchant being soaked to the tune of 100 denari for each of the gilded rhubarb pills that had been prescribed by his doctor.

- Apothecary Jar, earthenware with tin glaze (maiolica), c. 1550.

Apothecaries got away with charging the earth for their concoctions because of advertising, as much as anything. The shops were easily the prettiest in any Renaissance market, often with shelves of matching, brightly-colored maiolica pottery. Apothecaries would mix mysterious medicines out of these expensive jars, chattering away to clients about their rarity and purity and potency all the while. By the time they were through, the outrageous prices seemed justified. They’d even send you home with a little pot or gilded box all your own–which, of course, was then added to the price.