I know that you use parts of mythology but not necessary all of it in your books. Ray says that Caedmon is the son of Zeus. In Greek mythology Artemis is the daughter of Zeus. In your series is Caedmon Artemis’ half-sister on his father’s side and therefore Cassie’s uncle?

There’d be no way to use all of the Greek myths, which are voluminous and often contradictory. That’s what happens when you have a syncretic religion that borrows from every other mythology that it comes into contact with. Take Artemis, for example. The Greeks, who came from a very male dominated culture, had absolutely no idea what to do with Artemis.

Let me lay out their problem for you. First, Artemis didn’t begin with the Greeks. She was probably a relic of the great mother goddess cult that may have gone back as far as modern humans do. Remember this little cutie?

That’s the Venus of Willendorf, being thick and juicy. The statuette dates back—and this is not a typo—25,000 to 30,000 years. She’s one of many so-called “Venus figures” that have been unearthed at sites all over the ancient world. This one comes from Austria, near Willendorf, hence the name.

Many archeologists believe that they are evidence of a prevalent cult of the Great Mother in prehistoric/Neolithic times. That is borne out by the goddess Gaia (Mother Earth, basically) being one of the most important of the Titans, the group of gods who ruled until Zeus came along and defeated them. It’s also borne out by this:

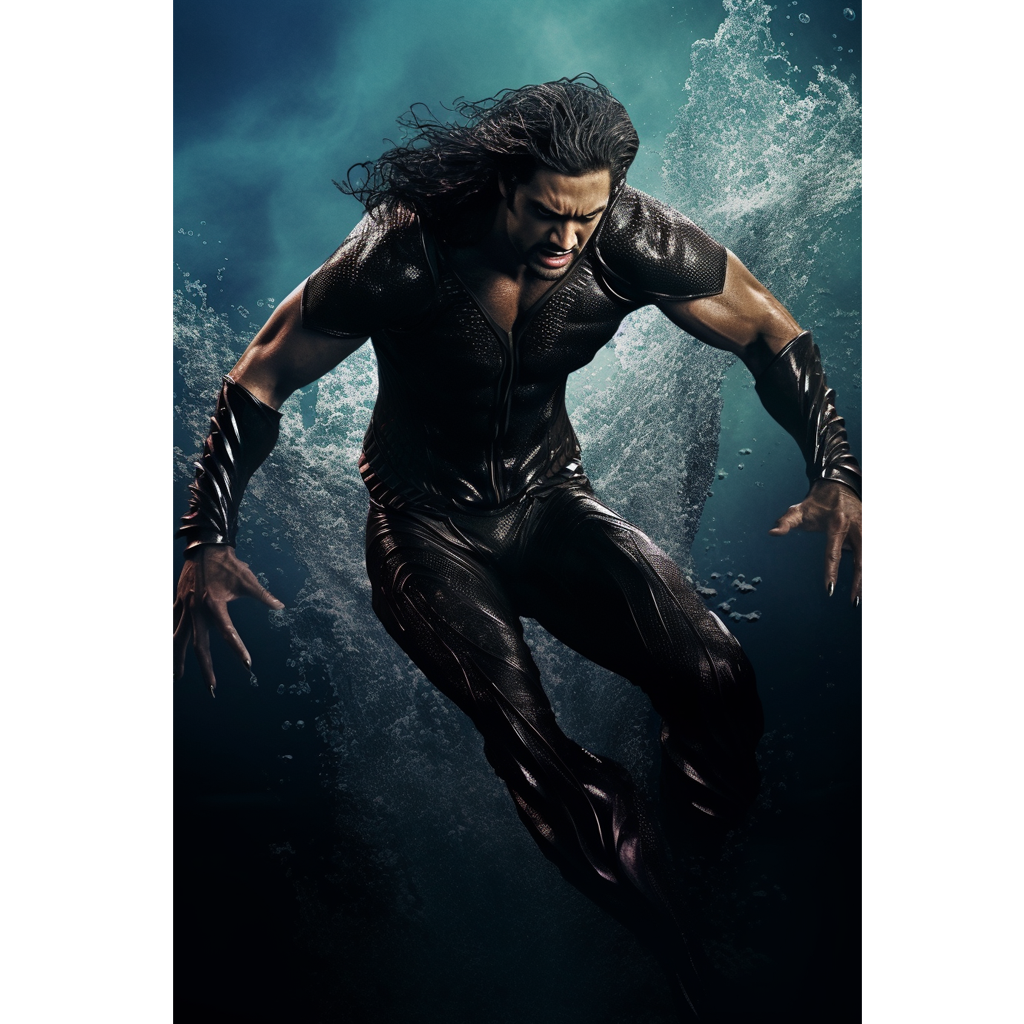

That is Artemis of the Ephesians, not the pretty young girl often depicted in Greek statues. Those, uh, protuberances on her chest? They are believed by some scholars to be extra breasts, to symbolize her feeding and nurturing the world. The animals carved onto her dress likewise show her dominion over the Earth. The Greek poet Homer, writing around 1100 B.C., was already referring to her as “Mistress of Animals”. She wears a crown on her head, and her necklace has the Babylonian astrological signs on it, thus also depicting her as Queen of Heaven.

The second problem faced by the Greeks was Artemis’s popularity. She was one of the most widely worshipped goddesses in the ancient world, with the number of her temples and cult centers rivalled only by those of Zeus himself. Her main temple at Ephesus, the Artemision, was considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Constructed entirely of marble, it took one hundred and twenty years to build, had columns sixty feet high, and was four times the size of the Parthenon, covering an area roughly the size of a soccer field. The Artemision was also the center of the Mysteries at Ephesus, a cult outside the Olympic one that elevated Artemis’s worship over that of any other god, including Zeus himself.

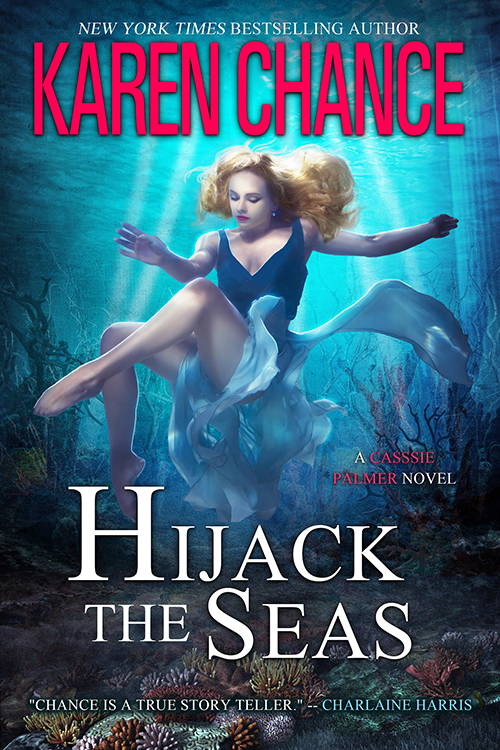

Third problem for the ancient Greeks was that Artemis was identified with a number of women-centered cults, and they weren’t shrinking violets. In mythology, she was the goddess worshipped by the Amazons, the famed warrior women of legend. That’s Penthesilea up there, the queen of the Amazons. She was such a deadly warrior that, when she accidently killed her sister and decided she wanted to die, she had to seek out the demigod Achilles to do the deed, as no one else could defeat her.

Likewise, the Spartans revered Artemis, and sacrificed to her before leaving on new campaigns. Perhaps related to this, the Spartan women were known for being some of the strongest and most outspoken in Greece. They were famed for exercising and hunting as much as their men, having equal inheritance rights–allowing some to build up great landed estates–and sometimes even becoming warriors themselves. Arachidamia, a 3rd century B.C. Spartan woman, led troops in battle, and other Spartan women were known to fight in sieges.

But Artemis wasn’t just associated with warrior women. Young girls from Athens often went to her cult site at Brauron in Attica where they participated in rituals honoring the goddess (AKA went to a nifty summer camp). That’s a statue of one of them above, unearthed at Brauron, holding a pet rabbit.

Artemis was often associated with bears (the original Mama Bear?) That may explain why the little girls were known as “Little Bears” (Arktoi). Older women frequented the site as well, to pray for children or for safety in childbirth.

Artemis’ main cult center at Ephesus was a locus of female power. There were fifteen women who served as chief priests of Artemis (archiereiai) composing the largest group of female priests anywhere in the world. The women seem to have held the offices in their own right, and not because of their husbands’ titles. Likewise, the cult of Hestia Boulaia, also in Ephesus, had at least twenty-eight women who served as prytanis, basically mayor of the city who presided over the town council.

Artemis is also a popular goddess with Wiccans today, because she was conflated with Hecate in Roman times, the patron goddess of the underworld and of witches. The three heads of the goddess above are Artemis, Hecate and Selene (another moon goddess) showing three faces of one deity.

So, we have an ancient mother goddess who was all about female power coming into conflict with Zeus, the head of a very male centered religion in ancient Greece, where women had very little power. So, what happened?

Well, as stated, the Greeks had no idea what to do about Artemis. She freaked them out; she really did. A goddess as powerful as that could give their women ideas. Something had to be done.

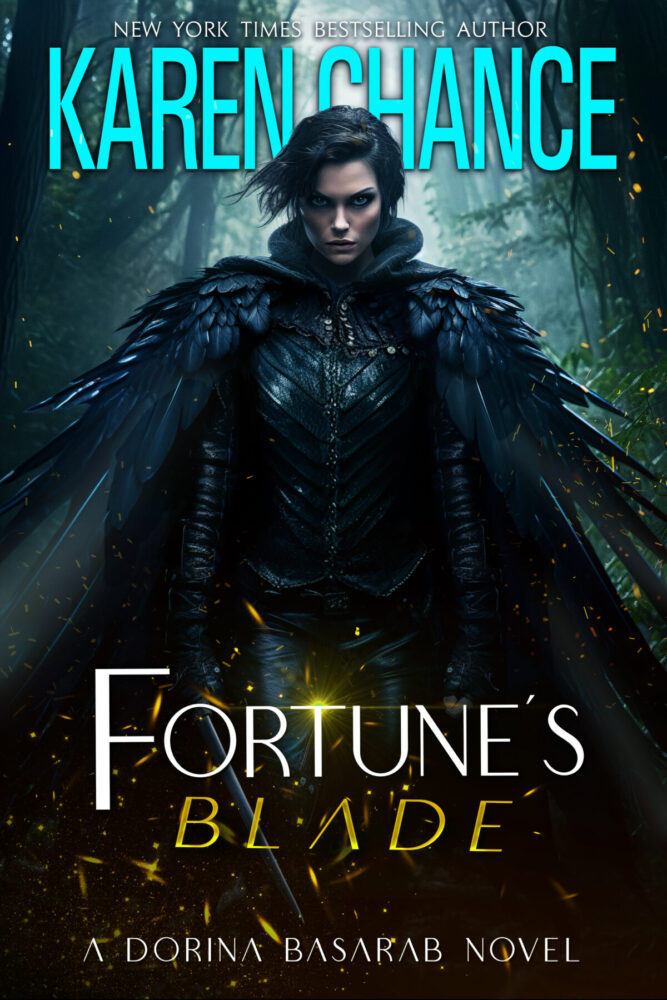

This is the Greek Artemis. Notice any difference? The Greek history of Artemis is an often-flawed attempt to make a powerful female goddess somehow fit into their world view.

The Greek Artemis did have some concessions made to her earlier version. She was a virgin goddess, so that no man would ever rule over her. That, of course, made her fame as a protector of women in childbirth difficult to explain, so she was said to have helped her mother with Apollo’s birth. The Greeks even agreed that, yes, she could fight pretty well, and a number of stories were told about her cleverness and bravery in battle. But they insisted that she was nonetheless subordinate to Zeus, the head god of their pantheon, even making her his daughter, perhaps because Greek fathers had basically total control over their daughters’ lives. They wanted to make it very clear that Artemis was just a tomboy type who was good with a bow and whose quirks were indulged by daddy Zeus, and not a model for all women.

But the truth was very different. In the ancient world, Artemis was not a daughter of Zeus; she was his rival. How that plays out in the books remains to be seen.

Leave A Comment